Episode 2

Manhunt

Atlanta’s search for a serial killer becomes more and more convoluted.

– Mike McComis, FBI

I’ve recently been told that if I release this podcast, “bad things” are going to happen to me in the sense of a threat on my life, or my safety, or that of my family.

– Neil Strauss, Journalist/Host

I’ve recently been told that if I release this podcast, “bad things” are going to happen to me in the sense of a threat on my life, or my safety, or that of my family.

– Neil Strauss, Journalist/Host

– Monica Kaufman Pearson, WSB-TV News Anchor

Victims

Christopher Richardson

Age 12

Last Seen 06/09/1980

Earl Terrell

Age 10

Last Seen 07/30/1980

Lubie Geter

Age 14

Last Seen 01/03/1981

Curtis Walker

Age 13

Last Seen 02/19/1981

Transcript

UGA Film Rep 1: What we have is raw news footage from WSB-TV. We have 17,000 hours of raw news footage. So far I’ve identified 614 clips, but we have about another 150 tapes to scrub through. The whole time I’ve been working on this collection, I’ve been thinking someday, someone was gonna come along and do this. It was you guys.

UGA Film Rep 2: Step aboard our Tartus. It’s bigger on the inside than it is on the outside.

Payne Lindsey: Where are we going?

UGA Film Rep 2: Down to the sub-basement, high density storage vault.

Payne Lindsey: It’s like a roller coaster.

UGA Film Rep 2: Yes. I can make it go fast if you’d like. It’s a 30,000 square foot facility, which we keep at 50 degrees Fahrenheit with a relative humidity of 30%. Thirty-two feet from floor to the ceiling, actually the top of our ceiling there is the floor of the second floor. Prior to us building this building here was a Native American settlement of some sort here, if I understand what people have told me over the years. Everything is shelved down here by size and then by barcodes.

Payne Lindsey: How many records do you think you guys have on the Atlanta child murders?

Intro:In Atlanta, another body was discovered today, the 23rd.

Intro: At police task force headquarters, there are 27 faces on the wall, 26 murdered, one missing.

Intro: We do not know the person or persons that are responsible, therefore, we do not have the motive.

continue reading

Payne Lindsey: From Tenderfoot TV and HowStuffWorks in Atlanta-

Intro: Like 11 other recent victims in Atlanta, Rogers apparently was asphyxiated.

Intro: Atlanta is unlikely to catch the killer unless he keeps on killing.

Payne Lindsey: This is Atlanta Monster.

Jim Procopio: Sketching back then wasn’t what it is today, I mean, some of these sketches they come out with, they’re better than photographs. Back then, you work with what you had and it was a pretty good sketch. We had a composite of who this guy would be.

Payne Lindsey: What’d it look like, do you remember?

Jim Procopio: Well, it was a black male with bushy hair. I remember the composite sketch very well. This is a folder of paperwork I kept from my time as administrative coordinator of the Atlanta child murder cases. There was an animosity between the local police and the FBI. One of the main things was the mayor, Maynard Jackson, he says, ” I want every living FBI agent, my police department is basically incompetent and they can’t solve it. We need the FBI to solve it”, so he threw his department under the bus. None of us wanted to get involved because it looked like just a local mess.

Payne Lindsey: This is Jim Procopio, but he goes by “Popcorn”.

Jim Procopio: … give it a fresh look-

Payne Lindsey: He worked for the FBI alongside Mike McComas during the time of the Atlanta child murders. Mike actually introduced me to him.

Mike McComas: You’d probably be interested in talking to Procopio. Popcorn’s a good guy. Now if you can get into his treasure trove, he’s got boxes of stuff.

Payne Lindsey: Popcorn dealt with all the records and files in the FBI, and just like Mike McComas, he stressed the importance of the composite sketch they received early on in their investigation, from a kid who told police that a man had tried to abduct him.

Jim Procopio: Well, it was a black male with bushy hair. I remember the composite sketch very well.

Payne Lindsey: After interviewing the kid, they were able to form a detailed sketch of the suspect, a black male with bushy hair. After only a few minutes with Popcorn, you get the impression that this guy doesn’t forget a thing.

Jim Procopio: And it goes back to another cultural, socio-economic issue. When Maynard Jackson became mayor, first black mayor in Atlanta, the first thing he said was “I want to make the police department more brown.” The police department, up at that time, had some black officers, several who were majors and above, but it was mainly a white police department. When the white officers heard that, they saw the handwriting on the wall, if you were white you’re not gonna rise rapidly in this department, it’s gonna be black. A lot of the older ones, they said, we’ll see ya, they retired. So consequently, they lost many of their senior officers, the best homicide investigator.

Jim Procopio: Then they had a big cheating scandal in the police department. They found out that a lot of the black recruits in the police academy were given the answers to tests, so that was another major scandal.

Jim Procopio: So the police department was left, in ’78, ’79, ’80, were relatively new and inexperienced. So I guess some of the homicide detectives were not that experienced and they missed the signs that there were commonalities in the 8 to 10 to 12. They had, by the time the Bureau got in, they were up to 14, 10 found, 4 missing. Further, the FBI does not investigate murders, murder is not a Federal crime. If it’s committed on a government reservation, it is. If it’s certain Federal authorities, it is. If it’s killed in the commission of a civil rights violation it is, but the Bureau doesn’t investigate murders like you have on the street every day, so we had no jurisdiction.

Jim Procopio: We went to the Atlanta Police Department and said, “we’re here to help you.” We were greeted by “yeah, right.” “We want all your files.” So I went through all the cases, we assigned either two agents or one agent per victim, and we had 14 of the victims at the time. So we said, go out and redo the case, look through it, give it a fresh look, come back and tell us what you find. About 10 of the 12 of them come back and said these look like local crimes and we were pretty much convinced that they were all local homicides that the APD had bungled. We didn’t see any pattern, we didn’t see anything.

Payne Lindsey: The FBI, along with local police, were not convinced they were dealing with a serial killer. But as the death toll of black children was growing, they began to recognize similarities in the murders. It would start with a child going missing, for days, weeks, and sometimes even months, and the FBI became involved in many of the searches. Popcorn recalled the first big search he was a part of.

Jim Procopio: There were 1,000 searchers all over the city. One place was Red Wine Road in south Fulton County. If you go there today, it’s right off 285. There’s a huge shopping center with a Target and a whole bunch of stores. Back then it was woods. About 3: 00, the team down on Red Wine Road says, “we found skeletal remains”, so everybody hauled ass and it was like being in Vietnam again. There were the news choppers overhead, they got wind of where we were, all the news choppers were overhead.

Jim Procopio: So I got there about 5: 00 and I parked my car on Red Wine Road and I walk in the woods and something catches my eye at eleven o’clock and I walk over and it was a skull and more human remains, so we had two human remains within a 100 feet of one another.

Jim Procopio: And this lead to one of the most bizarre episodes. About a 100 feet below both bodies, we found a Playboy magazine. It was that week’s Playboy magazine, it came out that Wednesday, this was Friday. So we found the Playboy magazine and there was a sticky substance between the pages, I’ll let you decide what that was. So we immediately fantasized, the investigators, the killer came back, came down here to site of the murders, masturbated and then took off.

Jim Procopio: This is key evidence. We packaged it up, raced it out to the airport, gave it to the captain of a Delta jet heading for Washington, DC. An agent picked it up as soon as the plane landed, rushed it to the FBI laboratory. They gave it to the lab, they developed prints and identified the sticky substance.

Jim Procopio: We didn’t have any of the prints on file, so we sent it to the APD to look at through their files. Within an hour, they identified the print. So we went in, we arrested the guy, we searched his house. We brought him to the Bureau, we polygraphed him, he passed the polygraph. “What the hell were you doing down there?” He says, “Well, my wife just had a baby, I went down there that afternoon.”

Jim Procopio: Now during that time we were part of the Vice President, George Bush’s, task force. Everything I wrote went to a Unit Chief at the Bureau, went to the Director, to the Attorney General, to George Bush. George Bush read it.

Jim Procopio: So the one thing he asked us was, “Please don’t tell my wife.” We said, “You god damn idiot. Do you know the Vice President of the United States knows what you did when you went into the woods and you’re worried your wife’s gonna find out.” By the way, we code named that, it was known as the Wood Wacker.

Payne Lindsey: Popcorn’s first big lead went nowhere. Popcorn had found the bodies of 11-year-old Christopher Richardson and 11-year-old Earl Terell. Christopher had been missing for eight months and Earl had been missing for six months. To me, on the surface, these cases seemed open and shut. A Playboy magazine with semen on it was found near the bodies, with the suspect’s fingerprints on it, but after an extensive interrogation, the suspect passed a polygraph test. And despite all the bizarre circumstances, the FBI was convinced that this man was not involved in the murders, so they moved on.

Payne Lindsey: Both Popcorn and Mike McComas told me that when the FBI got involved in these cases, there was an extreme tension brewing in the city of Atlanta.

Mike McComas: Of course, the blacks wanted it to be somebody white and the whites wanted it to be somebody black and, I can’t speak for the rest of the Bureau, but my partner and I, Larry Ellington, we talked about it a lot. First off, our profilers said that serial killers rarely cross races, they’ll kill in their own race and all these kids were black.

Payne Lindsey: Popcorn and McComis both mentioned FBI profilers, the people who formulate an idea of who the killer is, who the FBI should be looking for. And there was one characteristic that stood out to me immediately.

Jim Procopio: It had to be a black guy. A white man cannot go into a black neighborhood, pick up a kid, put him in his car and drive off without anybody seeing.

Mike McComas: If there’s a crime scene, then the media was just unbelievable. And with all the attention this case was getting, it was almost impossible to get into a predominantly black neighborhood and not be challenged or approached or whatever if you were white.

Jim Procopio: It just doesn’t happen. In fact, when we went into black neighborhoods during the investigation, everybody on the street was out on their front porch as soon as we appeared in the neighborhood.

Mike McComas: There was one place that I think is gone now, it was a housing project, they had what they called the Bat Patrol, and these were adults that walked around with baseball bats and looking for suspicious characters or protecting the community, whatever, but they called them the Bat Patrol. We were over in this housing area. We had two young black kids, that had supposedly seen something, we thought. So Larry and I were tasked to go over and pick up these two children and their mother.

Mike McComas: So here we are in the brown Ford again, and Larry’s driving, I’m in the passenger side. And we have the mother sitting in the middle and the two black kids in the back seat, near the windows, two young boys, and I think they were like 10 or something, 8, 10, 12, I don’t know, somewhere around that. And we didn’t get two blocks before we were boxed in by about three or four different police cars. And we weren’t proned out, but it was coming to that before we finally got them to look at our identification, hey, we’re FBI agents, because he goes, somebody had called in, there’s two wife guys with some black kids in the car.

Mike McComas: So it was tough getting in and out of certain areas, and so we were kinda convinced this guy had to be black. He had to be black, we just couldn’t figure out how he was getting them in the car.

Payne Lindsey: Was this a skewed opinion, coming from only white males? Was it that impossible for a white person to walk in the inner city of Atlanta in the early ’80s? I don’t know. I asked Eric and Jasper Cameron, they grew up in Atlanta during that time. If anything, they would know.

Eric Cameron: Personally I felt like it had to be somebody that could move around in the community. So therefore, I felt like it had to probably be somebody black or somebody who wouldn’t draw suspicion. ‘Cause you know over there where we live, a white person walking around over there, it’s gonna draw attention, ’cause that wasn’t happening then. Now, now you go ever there, it’s like everybody, but back then, naw, it would have drew too much attention, so I always felt like it probably was somebody who could move around pretty easy, undetected, without really causing a lot of suspicion.

Payne Lindsey: But not everyone agreed on that. This is Bernard Parks. He grew up in Atlanta, too, and was also a child at the time of the murders.

Bernard Parks: There’s certain guys that, they were around, it was like there weren’t a lot of white guys, right? But-

Payne Lindsey: But there were some.

Bernard Parks: Yeah. I mean like you grew up, you know what I’m saying, there’s was like one or two white guys that went to my school, right, but that’s just because they’re family didn’t have no money, right. So they was just around and so you kind of accepted them. But I always say, they got cousins, they got friends, they got people that hung around that we accepted. But it wouldn’t have been normal, though, in that time, for a black guy just to walk up and be accepting of a white guy without somebody understanding what’s happening, right. That just wasn’t normal, I mean, you just question period because you’re in my community and this ain’t your community.

Payne Lindsey: I asked Monica Pearson, the formal news anchor in Atlanta. Her memory was crystal clear.

Monica Kaufman: They weren’t looking for a murderer, they were profiling. They decided that that’s what it was and you have to keep all options open. I think any time you don’t open up and cast a wide net, you lose the opportunity of finding someone else who might be involved. It’s as simple as that, you have to look at all the possibilities. And if you start out by saying it has to be a black person who did it because these were black children, that that’s the reason why so many in the black community thought it was the Klan.

Monica Kaufman: I think that’s shortsighted on their part because you could easily have a white man in that community, dressed as black people dressed, and no one would notice him because he just looks like a black person, he’s in this community. Now most white people would not go into that community because they would stand out like a sore thumb. But if you assimilate, from the walk, to the clothing, to the attitude, to the speech, and don’t say it can’t be done. I’m just throwing it out there. I think that’s shortsighted to say a white person couldn’t do it. A white person could, if you know the community.

Monica Kaufman: You had a white guy graduate a couple years ago from Morehouse College as a valedictorian. White folks go into the black community all the time to buy drugs and they don’t have a problem fitting in. If you look like the people who live there, and your skin is just a little lighter than somebody else’s, it’s not gonna stand out. I think they’re wrong on that.

Payne Lindsey: From her perspective, the possibility of a white killer was ruled out way too quickly. I couldn’t help but think she made a good point.

Monica Kaufman: The one thing I remember most about the missing and murdered children, I still see that visual every day, is Maynard Jackson sitting there with piles of cash, offering a reward for any information on who was committing these crimes.

Maynard Jackson: Here’s $100,000 and it’s all yours.

Bernard Parks: Most gangster picture ever, him sitting with that money on the desk. I think that’s where they got the shot from for Ransom, remember when Ransom, they came and Mel Gibson, he put all that money on the table. He was like, “Now I’m putting this bounty on you.” That was Maynard’s line.

Payne Lindsey: I read about this over and over in my research, the reward money. It started with $100,000 from the city, but private donations, including one from Muhammed Ali, brought it to over $500,000. Today that would be around $1.5 million. As Atlanta struggled to find the killer, the city needed more and more money. One solution was a benefit concert.

Frank Sinatra: Come fly with me, let’s fly, let’s fly away …

News Reporter 1: Frank Sinatra will be joining Sammy Davis, Jr. on stage at the Atlanta Civic Center. The two figure to draw a standing room only crowd for the March 10 benefit concert to help the investigation into the crimes against Atlanta’s children.

Payne Lindsey: The city held a huge benefit concert to raise money for the investigation at the Atlanta Civic Center, but the FBI was on high alert for the killer.

Jim Procopio: I was convinced that that night he would respond to that and I was convinced in my mind that he would drop a body in the fountain right there.

News Reporter 2: Frank Sinatra arrived here at Charlie Brown Airport just a few minutes before 6: 00. He’s now on his way to the Atlanta Civic Center, where he’ll join Sammy Davis, Jr. for tonight’s benefit concert.

News Reporter 3: Sammy Davis, Jr. picked up a phone and volunteered to help Atlanta. Today, the superstar arrived here on his private jet.

Sammy Davis Jr: Such a horrendous tragedy as this affects, as I said, it certainly affects all of America.

Jim Procopio: I was there that night and we had cops and helicopters, there were cars everywhere, police cars everywhere, no one could have gotten in with a body.

News Reporter 4: It started with police dogs, sniffing the entire Civic Center, looking for explosives. The mayor’s office called this routine.

Payne Lindsey: Were you guys prepared to catch somebody that night?

Jim Procopio: Oh, hell, yeah, that’s why we were all out.

News Reporter 5: Officials have been preparing for weeks for this night. Extra security guards have been hired and extra police officers have been put on patrol here, with just one objective, to keep an eye on children.

Jim Procopio: It was overwhelming. The Atlanta Police Department out in full force. You had the GBI, the FBI was there, the task force, everybody was there. There was no way anyone could have gotten in there and done anything.

News Reporter 6: There were so many news people here coming from all over the world, Chicago, New York, Hamburg, London, so many, they had to be regulated to a room in the basement. Meanwhile, upstairs Atlanta’s finest started to arrive. But the high points of the show weren’t outside, they were in here.

Frank Sinatra: I’ve got the world on a string, sitting on that rainbow. I’ve got the string around …

Jim Procopio: Didn’t respond into anything. Got a lot of publicity, I thought he would respond, somehow he didn’t.

News Reporter 7: And while Sinatra was entertaining as he sang, he was most touching when he spoke.

Frank Sinatra: More of my tears are shed for the brothers and sisters and playmates of the victims, to whom terror has become an unwelcome companion. And to all of the fine decent people in Atlanta, who are frightened by day and doubly frightened by night, you have my prayers, that is, and that it should pass without further bloodshed.

Payne Lindsey: The city, as a whole, was banding together to catch this killer and every single law enforcement agency was working around the clock. All the murders were of black children, from the inner city of Atlanta, and they were disappearing from their own neighborhoods, in their own local hang-outs. One popular place in the city at that time for kids to hang out was called the Omni, an arcade room with food and a movie theater. But the Omni was also becoming a place where some kids were last seen.

Eric Cameron: That’s what we did. It was a game room and we literally would go to that game room and go to the arcades and all that, so that was like video games and stuff like. That’s what we did, we went to the Omni, hung out at the Omni.

Monica Kaufman: Friday night date night, get out of the house night, and the Omni is packed with youngsters.

News Reporter 4: The Omni Complex, a mixture of fine stores, sporting events, movies and game rooms, a popular place for the inner city kid to hang out. That’s why this special task force became interested in the complex as a meeting place. Investigators first started looking for some kind of connection back in February.

News Reporter 5: This sign went up today at Electronic America. The manager doesn’t want anyone 17 or under in here once 7: 00 hits. The owners realize such strict rules hurt their business, especially when their business attracts mainly teenagers.

Payne Lindsey: The 1980s saw the rise in arcades and video games, but another trend, and one I didn’t know about, was the 1980’s fascination with psychics. In fact, psychics even played in the Atlanta child murders. I heard a lot of weird stories surrounding this case, but so far, this seemed the most bizarre, a true example of law enforcement grasping at straws.

News Reporter 6: Police are now working with more than one psychic to solve the cases of six murdered and six missing children. This is how the nationally known psychics spent their Friday the 13th, they are visiting Atlanta courtesy of the National Inquirer. Yes, the same National Inquirer with those sensational headlines that can been seen at most supermarket counters. As the psychics scrambled through the woods where four of the 20 murdered children were found, psychic Micki Dahne of Miami kicked off her shoes. She asked reporters to feel how hot her feet were and then declared that two more bodies might be found nearby.

Micki Dahne: There’s something here, some child out there is trying to tell us to go further into this.

News Reporter 6: Jonathan Bell, whose brother Yusef is among the victims, also served as a guide. A freelance artist was there, too, sketching psychics’ descriptions of suspects.

Micki Dahne: I do not care at this point what they think of me. I’m here to get a killer off the street, if it takes one person or 5,000. My big thing is that if I have to do it alone, I will. I feel that they are afraid that if one person does it, how will they feel, and I can understand that, but I’m here more so for the children. And I do not want the reward money, that I will put in writing, I do not want the money. I’m not here for the publicity. I’m just like them, I want the killer off the street.

Payne Lindsey: One psychic gave police and news stations a detailed description of who the Atlanta child murderer was.

Psychic 2: He knows in the daytime what he’s dealing with, but at night, he’s not really sure. So he kinda stays to himself in his apartment. He has a television set, there’s no guns up there, no nothing. He’s very smooth talking when he does talk, which is very seldom.

Payne Lindsey: And he’s been seen by a lot of people.

Psychic 2: Oh, yes, there’s no doubt in my mind he’s walked beside probably some of the parents of these children. He’s shrewd, he’s methodical. You’re not dealing with a guy with 164 IQ. He’s clean, he’s neat, he’s above suspicion. You’re dealing with a methodical, a man that’s some systematic, but angry now, getting more frustrated. I cannot stop him, I don’t have the authority or the power.

Payne Lindsey: At the University of Georgia in Athens is the Walter J. Brown Media Archives, a huge multi-story facility that holds hundreds of thousands of archived documents. In the early 1980s, this was arguably the biggest news story, especially in Atlanta. I made a call to Mary Miller, one of the archivists, to see if we could access their news archives related to the case, and as it turns out, they have thousands of hours of raw news footage from WSB-TV, the local Atlanta station, material that hasn’t been viewed by the public since the early 1980s. In that time, nothing was digital, it was all on film or tape, but the team at the University of Georgia worked tirelessly to gather and digitize as much material as possible. And then they gave us a personal tour of their vault.

UGA Film Rep 2: Everything is shelved down here by size and then by barcode, so each thing that you’ll notice here, each item has a barcode on it and each shelf has a barcode and the items are linked together, so it gives us a barcode and we work by that.

UGA Film Rep 2: What we do with video tape is a little different from what we do with print materials. The video tapes will have to go into coolers, because they need to be acclimated from the cold, dry environment. When they move upstairs, it’s a little warmer and a lot more humid, so they have to go in the cooler so the temperature can come up slowly, they can acclimate.

UGA Film Rep 2: January 2012, when we opened to the public, we probably pulled about 150 to 160,000 items, and we’ve yet not been able to find everything that’s been requested. As I said, he’s gonna start coming this way, so we’re gonna need to start walking back this way.

Payne Lindsey: While searching the archives, I came across several news stories involving strange leads. This one, in particular, caught my attention.

Payne Lindsey: According to FBI documents, on January 8, 1981, an anonymous white male called the Rockdale County Sheriff’s Department, claiming that he placed the body of Lubie Geter out on Sigman Road. Then he threatened to leave the body of another child, but this time the child would be white.

News Reporter 7: An unidentified man who has been calling the Rockdale County Sheriff’s Department for the last few weeks, that man has told deputies they could find Atlanta’s missing children on Sigman Road. And we’ve learned that recently he’s also called and said he was going to harm some of the children in this neighborhood.

News Reporter 7: When the Rockdale County Sheriff’s Department arrived at the scene this morning, all they knew was they had something already very familiar to Atlanta investigators, the body of a black male around 14 years old, lying just off Sigman Road. There was no apparent sign of a struggle.

News Reporter 7: Sheriff Vic Davis would only say today his department and the others involved are again very interested in taped conversations with an unidentified male caller, the most recent call coming the day before the body was found. The man told Rockdale deputies victims could be found along Sigman Road.

Payne Lindsey: Someone was calling the local sheriff’s department, claiming to be the killer, even declaring where the next body would be found, but it seemed at that time the police didn’t give this much merit.

News Reporter 5: Some detectives say, since this latest body was found so far from Atlanta, they may be dealing with a copycat murderer. Or they say the killer or killers may have known that the Rockdale Sheriff was receiving crank calls about the missing and murdered children and so just decided to dump a body here to taunt police.

Sheriff Davis: We’re taking a closer look at the calls at this time, but we still feel that maybe just the publicity drew the actual killer to this area to dump a body.

News Reporter 7: Sheriff Vic Davis hopes today’s discovery and the calls are just coincidental.

Payne Lindsey: Then I found another story. The video was of a live newscast, featuring a church minister in Atlanta named Earl Paulk. He voluntarily called into a local news station to present this story and he was making some very eerie claims, his alleged interaction with the Atlanta child murderer.

Earl Polk: I have received several calls from a person identifying himself as the one responsible as the one responsible for these crimes. I did notify the authorities, but I should like to remind you that I stand ready to minister to you and we are protected and covered by the Constitution of the United States of America. I stand ready to be directed by you as to a place of meeting. I will minister to your needs and you will be protected and you will be covered.

News Reporter 5: For one thing, the voice on the phone was not the same one that has called before, so Polk says his first step was to determine how much the man knew.

Earl Polk: I said, “How many of the crimes are you involved in. He said, “Well, let’s put it this way, the first three, somebody helped me with them.” I said, “Well, is he not helping you any longer?” He said, “No.” I said, “Why did he quit?” He said, “Well, he got afraid, him and his wife got afraid and he left town.”

News Reporter 5: Paulk says the man told him he could prove he was the killer because he could show Paulk a piece of clothing belonging to Curtis Walker. Walker’s body was found just two weeks ago in a river about a quarter of a mile from Polk’s church.

Earl Polk: So I said, “Tell me how you got the kids to get in your car.” He said, “Well, I’ve got a van.” And he says, “I tell em I’ve got paint jobs to do and they get into the van to go to paint.”

News Reporter 5: Paulk then questioned the man about his motives.

Earl Polk: I said, “Well, what makes you do this, what caused you to do these crimes? Could you tell me that?” And he said, “Well, I’m impaled, or I’m controlled, or forced by voices to do it.” I said, “Well, why are you calling me now? Are the voices released you so you could call me?” He said, “Well, I don’t hear the voices right now.” I said, “Why are you turning yourself in, or why are you wanting to come see me now?” He said, “Well, I’m tired of running, I’m out of money and my wife is afraid.”

News Reporter 5: The man told Paulk he was speaking from or near a pub on Ponce De Leon Avenue. Paulk then asked him if they could meet at his church on Flag Shoals Road and the man agreed. About a half hour later, a van pulled into the parking lot across the street, but immediately sped off. Paulk says he thinks the man spotted some police cars at a nearby shopping center and may have thought he was walking into a trap.

Earl Polk: My purpose of even telling this story was hopefully that he would know that there was no trap set up and that perchance he may yet try to make contact.

Payne Lindsey: After hearing the many stories from the FBI and looking back on the news archives, I started to get a sense of how the general public must have felt in 1980, completely confused, an incriminating Playboy magazine, psychic involvement, bizarre phone calls, and that mysterious composite sketch of a black guy with bushy hair, but none of it was amounting to anything. The media coverage of Atlanta’s hunt for a serial killer was gripping the entire nation. But things were about to change when a local Atlanta policeman found what appeared to be the first signs of physical evidence.

Atlanta Police: We had a body, a young boy, behind a building and we found a fiber on him, just one fiber.

Payne Lindsey: You guys found that.

Atlanta Police: Yes. And I removed it off of his shirt and I think it was blue, maybe a quarter of an inch long. It looked like maybe a sweater or a blanket or something, just a piece of lint, took the fiber to the crime lab. That information leaked out through high ranking people to the media and, lo and behold, it wasn’t me. And they were putting anything they could grasp. The media were, at that time, you’re talking about vultures. Everybody wanted to be the one to know the little tidbit that nobody else knew.

Jim Procopio: The Atlanta Journal came out in early February with a story, the police are finding hairs and fibers on the victim. Well, guess where the next victim wound up? Stripped and in the river. And we were getting victims every 10 days.

Mike McComas: We’re starting to see bodies in several different counties. We probably need to come up with a method or come up with an idea or thought to where we can at least direct this guy, keep him from spreading bodies everywhere, in hopes, of course, of catching him.

Jim Procopio: What I thought was the dumbest idea I ever heard, when Mike McComas and his partner, Larry Ellington, came to me and says, “We’ve got an idea,” and I said, “Okay, what’s your idea?” And they said, “We want to cover the bridges ’cause it’s obvious he’s throwing the body off a bridge.” And I said, “Why is that obvious?” I didn’t know at the time McComis grew up in a small town in Tennessee on a river and I grew up in New York City, we didn’t know what rivers were.

Mike McComis: The reason is, is I don’t think he would drive down to the river because of the chances of getting caught. And besides that, I was raised on a river in east Tennessee and I know, to get something to float down the river, you’ve got to get it out in the middle of the water or you stand a good chance it’s just gonna come right back to the bank.

Jim Procopio: He knew that, if you threw something from the shore, it eventually floats back to land. But if you throw something off a bridge in the middle of a river, it’ll float down the river. And I says, “Well, how do you know which bridge?” He said, “Well, we’re gonna pick 14.” I said, “How do you know you’re gonna pick the right one?” And he looked at me and he said, “You got a better idea, dumb shit,” and I said, “Not at the moment.”

Mike McComas: There was two rivers then, there was the South River and the Chattahoochee River, and I recommended that we stake those out, the bridges, because I felt that that was how he was getting the bodies into the water was throwing them off river bridges because it would be quick, it would be fast. He would get them in the water and it’s a good chance they would float downstream quite a ways. For my idea, I got rewarded of kinda supervising the detail. It was started every night around 6: 00 pm and we quit every morning about 6: 00.

Jim Procopio: It started toward the end of April, first of May, and we gave them 30 days. We actually had about 140 people total because we had to cover all night and we had to cover weekends, so we had 140 people assigned.

Mike McComas: And we were burning 140 bodies a night, too, because we had so many bridges on the South River and so many bridges on the Chattahoochee River. And what we did was, is we had two people on the ground under one side of the bridge, two people on the other, and then we had two chase cars per bridge. So if anybody dropped something in, the people underneath would notify the chase cars and that’s the way it happened. It was quite taxing, I mean, you’re going seven days a week, twelve hours day, it’s tough. I was single. The married guys, I don’t know how, with families, I don’t know how they did it, but I was single at the time, so it didn’t really have that much of an effect my home life, of course. Social life, yeah, but not the home life.

Mike McComas: But like I say, we were using 140 bodies a night. As a matter of fact, there were so many bodies that we had to go to the police academy and they gave us several recruit classes that hadn’t graduated yet, so the only thing they were allowed to carry was batons and flashlights ’cause they weren’t qualified on firearms. So, I mean, that’s how many bodies we were burning and that’s why they decided that it was gonna have to come to an end because we were just really wearing out manhours and nothing came of it.

Payne Lindsey: As an officer with the APD at that time, Mike Tovey remembers this bridge stakeout.

Mike Tovey: And we had just about every bridge, I think every bridge in Atlanta area covered. They canceled our off-days and we worked ungodly hours, like 5: 00 to 5: 00 in the morning, no off days, and we had people under the bridge. We had people on the water, posed as fishermen, and just about every bridge in Atlanta and even Fulton County. We patrolled it in rams, we had our guns in the boat with us, and really we were just grasping at straws, but it was apparent these bodies were coming over the bridge.

Payne Lindsey: On the very last night of the bridge stakeout, something happened that would change the course of their investigation forever.

Jim Procopio: Last night, last bridge.

Mike McComas: That night we set up, knowing this would be the last day. I had about six or eight bridges, I can’t remember, that I kinda kept an eye on, and if anybody had any problems or if somebody didn’t show up or logistical problems, whatever happened, and I was to be notified regardless. I was at a small bridge south and I heard some radio traffic and, at the time, our radios weren’t as good as they are today, and I remember getting on the radio and asking what’s going on and all I heard was something about a splash. I had a ’77 Ford LTD with a 400 big block in it and I can tell you I scorched tires getting up there ’cause I said something’s happened and I just felt it. We went racing to the James Jackson bridge and, as I was heading that way, the traffic started coming in a little clearer because I was getting closer.

Mike McComas: The gist of the story was is that the splash was heard by the police cadets, the guys that had to leave the academy early to work with us. We had two people under both sides of the bridge and, of course, we kept them hidden out, so they brought everything they needed for the night because they weren’t going anywhere. And then, in close proximity, we had a chase car on each side of the bridge and they, too, blended in so that they couldn’t be seen.

Mike McComas: When they looked up on the bridge from under it to see what caused the splash, the car appeared to be just starting up again, like it had been stopped and it was going two or three miles an hour, then crossed the bridge, circled around I think a convenience store. Then as he came back, that’s when our cars tagged him.

Mike McComas: We went up the exit ramp, went across the bridge and then went down, saw the cars sitting on the other side, they were on the southbound side and we were heading north, and I saw that there was several blue lights over there with a white station wagon that was pulled over. Since I was supervising it, and I had the ranking Atlanta police officer on scene with me, when we got there we were immediately briefed. I asked did they get his ID and they said yes, he was still sitting in his car and I still had my composite sketch and I pulled it out. He had these little glasses on and I drew the glasses and I held it up and I said, “Anybody recognize this guy?” and it was Wayne Williams to the tee. I mean, it was just Wayne.

Payne Lindsey: Next time on Atlanta Monster.

News Reporter 8: It was the predawn hours of May 22nd. The Atlanta Police Bureau and the FBI had been staking up bridges along the Chattahoochee River for the last two months. An Atlanta recruit heard a splash. Several radio messages and a flurry of activity soon had a car stopped. In it was 23 year old Wayne Williams. People who know Williams say he is a highly intelligent young man, a good student when he was in school.

Mike McComas: I went up to him and identified myself as Special Agent of the FBI and I asked him immediately if he knew why he was being pulled over. And he said yes, it’s probably because about those kids that are missing. It kinda surprised me, that was an unusual answer I thought.

Dwayne : It’s like I didn’t want to go, but this rabbit hole is very, very, very deep.

Payne Lindsey: Atlanta Monster is an investigative podcast told week by week, with new episodes every Friday, a joint production between HowStuffWorks and Tenderfoot TV. Original music is by Makeup and Vanity Set, audio archives courtesy of WSB news, film and video tape collection, Brown Media Archives, University of Georgia Libraries. For the latest updates, please visit atlantamonster. com or follow us on social media.

Payne Lindsey: Why do they call you Popcorn?

Jim Procopio: When I was in Memphis, a first office agent, brand new out of the FBI Academy, and Andy was my training agent. Andy was about seven or eight years older than me, a little more experience in the bureau, and Andy had a three year old daughter, Karen, who’s now in her 50’s, and she couldn’t say the last name Procopio. What came out was Popcorn, she called me Popcorn, Mr. Popcorn, and it stuck.

Payne Lindsey: Do you like Popcorn?

Jim Procopio: Sure.

More Episodes

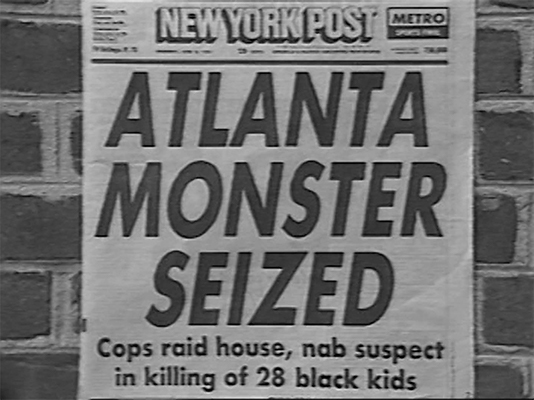

Episode 3

Atlanta Monster Seized

Atlanta asks, who is Wayne Williams?

Episode 4

Gemini

Wayne Williams through the eyes of those seemingly closest to him…

Episode 5

Wayne’s World

Payne makes contact with the alleged Atlanta Monster.