Episode 10

Loose ends

In this case, the truth depends on who you choose to believe.

– Tony

I’ve recently been told that if I release this podcast, “bad things” are going to happen to me in the sense of a threat on my life, or my safety, or that of my family.

– Neil Strauss, Journalist/Host

I’ve recently been told that if I release this podcast, “bad things” are going to happen to me in the sense of a threat on my life, or my safety, or that of my family.

– Neil Strauss, Journalist/Host

– Vincent Hill, former police officer

Victims

William Barrett

Age 17

Last Seen 05/11/1981

Clifford Jones

Age 12

Last Seen 08/20/1980

Larry Rogers

Age 20

Last Seen 03/30/1981

Joseph “Jo Jo” Bell

Age 15

Last Seen 03/02/1981

Transcript

Automated: You may start the conversation now.

Wayne Williams: What in the world? Hello, stranger. I’m finally out the hole and everything. I’m doing great. They let me out yesterday. It was the craziest thing. How the incident happened, boy, will be a separate podcast itself, but you will never believe. Maybe it’s a good thing it went down, because a lot of roadblocks got out of the way, and a lot of roads got opened, Payne.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne was out of the hole, and my daily calls with him were now back in full swing.

Wayne Williams: They let me out yesterday. And they were aware of the publicity and all. They said, “Yeah, it’s going good,” and all that. They were telling me they’d been following it all and all. They explained it. I sat down with the warden and all three of them and I explained the whole project, what we did. He said, “I’ll tell you what, Wayne,” he said, because I explained to him, I said, “I’m not out trying to talk to no … ” I said, “We’re trying to do stuff to get … ” He said, “I don’t blame you.” He said, “The people you need to get in here to see],” like TI like Payne he said, “You get with me and the lawyer and I’ll make it happen.” They put me back in the same dorm, back here with everything. They did a complete reset.

Payne Lindsey: It had been a month since I last talked to Wayne. Before I could ask him anymore questions, it was strictly business. He first set up a conference call with Dewayne and I.

Dewayne Hendrix: Hey, what’s up, man?

Payne Lindsey: Hey, what’s up, man?

Dewayne Hendrix: Hold on one second. Wayne is on the other line.

Wayne Williams: Yeah, I’ve got Dewayne here, Payne and I. I want to reiterate the same thing with Dewayne on the line, what we said, to make sure that everybody’s on the exact same page. Nobody speaks for Wayne but Wayne, but I’ve delegated Jimmy to handle all the contacts regarding the attorneys and the legal affairs on that so Payne understands what I said.

continue reading

Wayne Williams: Anything regarding the release of documents or anything about the case needs to come through Dewayne, because Dewayne is the most knowledgeable on this case. Like I explained to Payne, you the only person that can actually walk with him in these neighborhoods, introduce him to the people he’s gonna really need to see, because they’re not gonna talk with him otherwise, to beat the bushes and all.

Wayne Williams: Anything regarding my legal case, the way where I’m delegating the things, man, regarding the legal case and contacts, you go through Jimmy on all of that. He’ll make that happen. Anything regarding the documents or whatever, we have to go through Dewayne. See, these are the two people I trust to do that.

Payne Lindsey: The podcast was airing now, and it seemed like it was making Wayne a little antsy. Next he set up a conference call with his friend Jimmy.

Wayne Williams: You gonna have to get with Jimmy. He’s gonna have to take you to meet all of these different people and all that. This takes money and gas. You understand what I’m saying right there? Dewayne’s gonna do the same thing. You’re gonna meet suspects. You’re gonna meet people who are eyewitnesses to these things, but they have to take you in the hoods that you can’t go in. Not being funny, Payne, but being a young white boy, there are places you can’t go by yourself with this. Are you understanding what I’m saying?

Automated: You have one minute left.

Wayne Williams: They’re my eyes and ears to get it right. They’ll be able to tell you, “No, it didn’t happen this way. Yes, it did happen that way.” Don’t bother what any of them say unless you hear that from me. They could give you input and all, but basically, the ball stops with me, Payne. That’s what I’m trying to say.

Dale Russel: Wayne would’ve never been convicted if he was smarter, but the reason Wayne was convicted was because of what he did on the stand, when he went off the way he went off in court. Now part of it was it was Mary Welcome, his attorney’s fault.

Dewayne Hendrix: The first two days that Wayne was testifying, he was cool. They was asking him questions about being gay and all of this different stuff. He was saying, “Look, man, I don’t know nothing about that stuff. I didn’t do this. I wasn’t there.” He was cool, calm, and collected. The defense attorney told him to fight back on the stand, and that’s what ended up really getting Wayne getting the guilty verdict, because people were like, “No, he is a Dr. Jekyll, Mr. Hyde type person.”

Wayne Williams: What made her come to me and do that was a news story Channel Five ran. He said, “Wayne Williams appears too cool and calm.” They were responding to a darn news story. God almighty. She told me, “Wayne, you need to be more forceful. You’re looking too calm and cool.” Mary threatened to quit if I didn’t do that.

Intro: In Atlanta, another body was discovered today, the 23rd.

Intro: At police taskforce headquarters, there are 27 faces on the wall, 26 murdered, one missing.

Intro: We do not know the person or persons that are responsible. Therefore, we do not have the motive.

Payne Lindsey: From Tenderfoot TV and How Stuff Works in Atlanta.

Intro: Like 11 other recent victims in Atlanta, Rogers apparently was asphyxiated.

Intro: Atlanta is unlikely to catch the killer unless he keeps on killing.

Payne Lindsey: This is Atlanta Monster. The first thing I asked Wayne was about the trial, when he lost his cool on the witness stand.

Wayne Williams: You gonna find out all of what’s happened behind the scenes on this.

Dewayne Hendrix: Wayne doesn’t agree with this, but this is my theory behind that. I really think that she was a plant.

Payne Lindsey: Dewayne’s convinced that Wayne’s attorney, Mary Welcome, was some sort of plant, but he had no evidence to back that theory. Even Wayne himself disagreed.

Wayne Williams: I was the one that chose Mary. They didn’t choose her. That was a spur of the minute, because I had known her before, and I’m gonna be honest with you, I liked her as a person. I was drunk over her. That’s why I picked her.

Dewayne Hendrix: She was fine, but that’s one of the things they do.

Wayne Williams: They didn’t bring her to my attention, Dewayne.

Dewayne Hendrix: She was fine. She was fine as hell.

Wayne Williams: She was fine. She was fine. I’m gonna call back one more time. I’m gonna call back one more time.

Payne Lindsey: Apparently, Wayne was pretty fond of Mary Welcome. I asked him about the blowup on the witness stand.

Wayne Williams: This was I think my second day on the witness stand. There was a article in the paper and in one of the TV stations that said I was being too calm and cool on the witness stand. My attorneys saw that, and they were saying that we need to do something. They were saying that we were losing the jury, I was coming off being too calm and collected, whatever behavior that means.

Wayne Williams: Finally they said, “Wayne, we need you to be more forceful and protect yourself.” I said, “How do I do this? How do you try to present yourself in such a way?” Because I don’t think most people realize there isn’t a story book, there isn’t a guide to how you respond on the witness stand. I don’t care what people tell you about what type of preparations you’re going through.

Wayne Williams: I just responded. I was so upset that I could sense that that was a tragic mistake, because people thought I exploded. No, I was well under control. I wasn’t upset at the district attorney, so to say. I was upset at my lawyers, who put me in such a tragic situation. That’s what my frustration was all about.

Payne Lindsey: Do you think that that played a big role in your conviction?

Wayne Williams: No doubt. No doubt. We talked to a lot of the jury members afterward, and believe it or not, you could actually see the look on their face, I could sense it, they were like, “Oh my god.” I literally played myself out of stupidity into the DA’s hands, and it was the turning point in the trial, we found out later on.

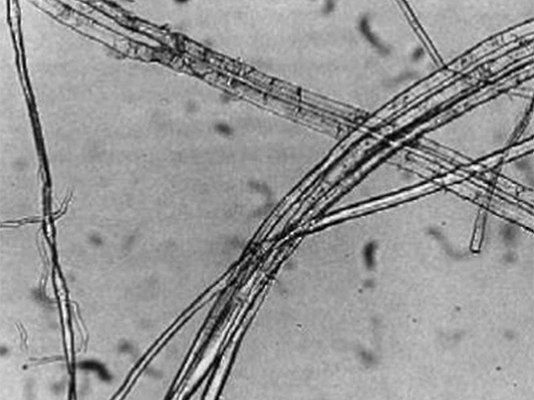

Vincent Hill: In talking to Wayne and looking at the evidence of this case, this entire case was built on fiber evidence. There were no fingerprints. There were allegations that some of Wayne’s victims were at his house or in his car. Not one fingerprint was found in Wayne’s house? He was that methodical that he cleaned all of these fingerprints? No neighbors ever said, “Hey, we saw these little boys going into Wayne’s house.” Prison, right? If Wayne was not on that bridge, the case would’ve been solved a different way or it would still be unsolved. Take that bridge out of the equation and what do you have?

Payne Lindsey: Vincent Hill reiterated several episodes back the overall importance of the bridge. Fiber evidence aside, if you take the bridge out of the equation, you don’t have Wayne to begin with. Let’s listen back to Wayne’s version of the bridge incident, from one of my first calls with him.

Wayne Williams: I was doing some pictures and on the 21st, the afternoon of the 21st, that was the first time I ever talked to her, about 3: 30 to 4: 00 briefly. That’s when she said, “I want to audition.” I said, “Before you audition, we need to do a interview.”

Newscaster 1: He tried to persuade the jury he really was out near a bridge that night, looking for a Cheryl Johnson, who still remains a mystery to this trial. The state implied he fabricated the story, but Williams didn’t budge from it, claiming the woman simply gave him a wrong number and wrong address.

Wayne Williams: I was suspicious because the information she gave me, being from Memphis, Tennessee, I said, “Oh, you should know some people I know in Memphis.” I called some names and she didn’t know them. That raised a red flag. She said, “Why don’t you come by the apartment where I’m staying with a friend? I think she said about 7: 15, “I gotta be at work at 8: 00.” That’s when she gave me the address. I said, “You sure about this address?” She said, “Yeah.” I said, “Okay, I’ll see you tomorrow morning.”

Wayne Williams: As a matter of fact, if you look at my statements, I even tell the police, I said the only reason I checked the address was because I felt it was a fake address that she gave. That’s why I went out to check it in the first place. I’m not even sure that’s her name. That was just the name that she gave me. We was doing public auditions. A lot of people gave fake names and fake addresses. I think all the hoopla over Cheryl Johnson is needless. She was obviously a prank call.

Payne Lindsey: The prosecution claimed that Wayne Williams had fabricated the entire story of Cheryl Johnson, saying she was fake, and now, years later, Wayne agrees. He was receiving hundreds of calls for music auditions, and every so often he’d get a prank call, this being one of them. Regardless whether or not Cheryl Johnson was a prank call, Wayne still claims that she called him, at least somebody did. Over the course of a few weeks, I kept asking him about it, trying to pinpoint an exact timeline for everything. According to Wayne, it starts like this.

Wayne Williams: She originally did not call me. This was a key point. She called my mother and left a note. My mother left a note. This was on the 20th I believe now.

Payne Lindsey: According to Wayne, Cheryl Johnson originally did not call him. She called the number on Wayne’s flier, which at the time was his house phone. He wasn’t there, so his mother answered. This happened the day before the bridge incident.

Wayne Williams: Anytime somebody called about a audition and I wasn’t there [inaudible 00: 11: 55] to do it, she would just write a post-it note for that, that’s all. I talked to her the next day. My mom was the one who wrote the call and stuff. My mom wrote that.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne’s mom took the call from Cheryl Johnson the day before the bridge incident and wrote down her information on a slip of paper to give to Wayne. What exactly did Wayne’s mom write on the piece of paper?

Wayne Williams: She just wrote a note, the callback number, that’s it.

Payne Lindsey: Your mom wrote down her number.

Automated: You have one minute left.

Payne Lindsey: Then where’d you get the address from from her?

Wayne Williams: It was on the note.

Payne Lindsey: On the note his mom left him was Cheryl Johnson’s name, phone number, and her address. Wayne did not make contact with her until the next day, around 4: 00 p.m., on the same night of the bridge incident. According to Wayne, he didn’t call her. She called his house phone again, but this time he was there to answer it.

Wayne Williams: Then the next day, she called back about 4: 00. That’s when I answered. I figured something was wrong with this woman, because her information didn’t add up. It didn’t add up.

Payne Lindsey: This is where things start to get a little confusing, so I’ll do my best to break it down. Wayne says the next day he didn’t call Cheryl Johnson back, but she called his house phone again, even though Wayne had the information to call her back himself. With so much emphasis on the note from his mom, it seemed odd for him to point out, so I asked him about it again, just for clarity.

Wayne Williams: No no no, she called me, Payne. I answered the phone. I don’t know what number she called from. I did not call her back. That’s what I’m saying. I talked to her who this woman claims she was on the afternoon of the 21st, about 4: 00. We talked for about maybe five minutes.

Wayne Williams: When she mentioned the address, that’s when she was talking about, “I gotta be at work.” I said, “We need to do not an audition like that, but a interview.” I said, “We gotta do an interview before you audition.” That’s when she was talking about she gotta go back to Memphis. That’s when I started questioning her on Memphis. I said, “You oughta know so-and-so.” She didn’t know anybody I mentioned the names in Memphis. My radar went off at that point, because I knew quite a few people in the music business in Memphis, and she didn’t know any of them. Strange. That was the only time I talked to this woman who claimed to be Cheryl Johnson.

Payne Lindsey: He talked to her around 4: 00 p.m. that day for about five minutes. He claimed he was already a little suspicious of her, but he agreed to meet her the next morning at her apartment anyway. He said that phone call was the first and last time he ever talked to Cheryl Johnson.

Payne Lindsey: Your mom got the call from some Cheryl Johnson, and then she wrote down the number and the address?

Wayne Williams: The callback information, right.

Payne Lindsey: Did you have that note with you when you went driving out that night?

Wayne Williams: Right. That’s the note. Right.

Payne Lindsey: Did you take the note with you?

Wayne Williams: Let me explain. I put it on my clipboard. I had about eight notes on that. In other words, Payne, we did the … If it hangs up, I’ll call you back. If it cuts off, I’ll call you back.

Payne Lindsey: After confirming his appointment with Cheryl Johnson the next morning, Wayne left his house later that night to go find her address, because he was still convinced she was a fake caller. When he left his house, he brought with him the slip of paper his mother wrote down her phone number and address on.

Payne Lindsey: The night of the bridge incident, what time did you leave your house that night?

Wayne Williams: I left about 6: 30 to pick up Willy Hunter.

Payne Lindsey: His first stop that night was not to go find Cheryl Johnson’s address. He left around 6: 30 p.m. to go to a recording studio called Hotlanta Records to drop off a bill for photo shoot services.

Wayne Williams: We went straight to College Park to meet Melvin Ware, Jackie Gato, and the people at Hotlanta Records, College Park, down there by the airport, to deliver the bill for the photo services I had done. We stayed there for about an hour. I left there about 7: 45. I never will forget it was a Thursday, because I had to rush back home and get the car to my dad because he had a Kiwanis Club meeting that night. He was late getting to the meeting because I had to drop Willy off first. When I got back, it was about 8: 00, maybe a little after 8: 00. I took Willy Hunter home first and took the car to my dad.

Payne Lindsey: After you left the Hotlanta Records, where’d you go after that?

Wayne Williams: I went home.

Payne Lindsey: It’s now around 8: 00 p.m., and he’s back at his house.

Payne Lindsey: You got home at 8: 00, and then when did you leave the house again?

Wayne Williams: About 1: 00 that morning.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne says that he didn’t leave the house again until 1: 00 a.m. that night. In the FBI case files, Wayne recounts his version of what happened that night, from that point forward. This is how it reads verbatim from the FBI documents.

Payne Lindsey: “When asked to recount his activities on the night of May 21st, 1981, William stated that he had stopped at the Sans Souci Lounge on West Peach Street to see Wilbur Jordan. Williams was attempting to pick up a tape recorder which he had loaned him. Williams recalled that he had talked to a female, who he stated was in his 40s, and who was taking admission. The individual informed Williams that Jordan had been in but was not around at the time. Williams left a message with her regarding the tape recorder and then drove to Smyrna, Georgia in attempt to find Cheryl Johnson’s address.” I asked Wayne about this.

Wayne Williams: When I went out, my intention was to go to the club about 1: 30 that morning, but to get the recorder. My intention was, I said, “Before I go to the club, let me check on this address first.” That’s when I made the trip up to Cobb County and all of this started transpiring.

Payne Lindsey: According to FBI documents, Wayne made a stop first at a club called Sans Succi Lounge.

Wayne Williams: Payne, I’ve got statements I can send you where … I never made statements to anybody. I was going to the club. That was my intention to get the recorder. I didn’t go to the club until the night of the 22nd.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne said he left his house with the intention of going to the club, but before he made it there, he decided to go check on Cheryl Johnson’s address first. Contrary to the FBI reports, Wayne says he did not go to the club the night of the bridge incident. Instead, he went the following night, the night of May 22nd. This whole thing was confusing, so a few days later I asked him about it again.

Wayne Williams: What I did when I went out there that night, I went to Sans Succi first. Understand what I’m saying?

Payne Lindsey: Yeah.

Wayne Williams: After I left home, I went to the Sans Succi first. I asked for Wilbur Jordan. I keep forgetting his name because he’s dead now. That was when she said, “He’s busy.” I said, “I’ll be back later.” I left there and I went back on I-20. I was gonna go home, but I said, “No, let me check this address.” I went I-20 to I-285 and went up there to find this address. This would’ve been I’m guessing about 2: 00, something like that.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne’s version of the story had changed. Now he’s saying he did go to the club that night, the same night he was pulled over on the bridge. Which one was it?

Vincent Hill: I heard different accounts too, right out of Wayne’s mouth. One thing that’s really important, being a liar doesn’t make you a killer. People lie all the time, doesn’t make you a killer.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne certainly told me two completely different stories about the Sans Succi club, so a few days later I asked him about it again.

Payne Lindsey: I’m confused about when you went to the club. One time you told me that you went to the club before the bridge, and then one time you told me that you went the next day.

Wayne Williams: Let me correct that so we’ll understand. What all the confusion over the club was that I went to the club first. Before the bridge incident, I went to the club looking for the manager who was a friend of mine. As a matter of fact, he was a co-producer with my music company. I did not go to see him, but yet the FBI in the statements tried to turn around and claim that I went to the club and saw Gino Jordan. I never said that. I never saw Gino that night. What I did was the next night after the bridge incident, which would’ve been the night of the 22nd, I went to the club and saw Gino Jordan. I was going down to pick up a tape recorder. I did see him the next night.

Payne Lindsey: Another thing Wayne had pointed out to me in our very first conversation about the bridge was something about his handwriting and the phone number for Cheryl Johnson. You may remember this.

Wayne Williams: All the confusion in the statements was over the thing on the telephone number and Cheryl Johnson. The number wasn’t 934-7766. You’ll see when I get my writing. I’m gonna send you some samples of it. It was 434-7766. My fours and my nines look alike because I close the loop at the top of them.

Payne Lindsey: The 4s and 9s were mixed up, because his handwriting looked the same on the note.

Wayne Williams: No no no. Nah, you ain’t hear me, Payne, the number I wrote was 434- 7766. They, in looking at my notes in the car and my writing, thought it was a nine. My nines and my fours look … I can’t tell the difference. They assumed that my writing was 934, and that incorrect information lasted to this day. That’s where the confusion came in on it. That’s why the note was so important, because the note would’ve shown it was 434, not 934.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne had told me earlier that his mother wrote the note, the same note he brought with him in the car.

Payne Lindsey: Your mom got the call from Cheryl Johnson, and then she wrote down the number and the address?

Wayne Williams: The callback information, right.

Payne Lindsey: Did you have that note with you went you went driving out that night?

Wayne Williams: Right. That’s the note, right.

Payne Lindsey: Did you take the note with you?

Wayne Williams: Let me explain. I put it on my clipboard. I had about eight notes on that.

Payne Lindsey: How was that possible? Wayne’s theory about his handwriting would only make sense if he had written the note himself, but he didn’t. He said his mom did, unless there was a second note.

Wayne Williams: I had an appointment book with me at the time. To be honest with you, I can’t remember if I actually had the note from Cheryl Johnson with me that night or a notation on my appointment book. I’m pretty sure it was a notation on my appointment book that I showed the FBI agent.

Wayne Williams: On the note that the FBI agents got, that wasn’t my mom’s handwriting.

Payne Lindsey: Before Wayne was stopped on the bridge, he claimed he had pulled over into a liquor store parking lot and used a payphone in attempt to call Cheryl Johnson.

Payne Lindsey: You called the number, and what happened when you called the number?

Wayne Williams: When I called the number that I called over there, the first time I got a doo doo-doo doo, “This number not in service.” I dialed another number, and then I think it was 967 or something. I can’t remember what. I tried three or four numbers. Finally I called one number, it looked like I woke somebody up, and said, “May I speak to Cheryl?” “She ain’t here!” and hung up the damn phone like that, not to say it was the right number. The person said, “She ain’t here!” and just slammed the phone down. I woke somebody up, and I didn’t try no more after that.

Payne Lindsey: This story does match the FBI reports, but I was still confused about the handwriting story and the mix-up on the phone numbers, so I asked him about it again.

Payne Lindsey: The FBI tried to call the number, right, and then said it didn’t work or what?

Wayne Williams: No no no, Payne. They tried to call 934. I dialed 434. Are you understanding what I’m saying?

Payne Lindsey: Yes. They called the wrong number?

Wayne Williams: Right. They tried it. I never called the 934. That’s them. The number I called was 434-7766, and I got a doo doo doo, “Number not in service,” or something. I can’t remember now. I tried, because it wasn’t but about a minute, and I tried a couple of more combinations and all, and finally I got one where somebody answered. I said, “May I speak to Cheryl?” “She ain’t here!” and slammed the phone down like that.

Payne Lindsey: The number that you had, the one that they got wrong, do you think the number that you had was her correct number?

Wayne Williams: I don’t think any of it was correct, Payne. That’s the point I’m making. I think she was a bogus call from the beginning. That’s my point.

Vincent Hill: I think the Cheryl Johnson was just some story he made up really quick, 2: 00 in the morning. Wayne could’ve said 100 different things besides Cheryl Johnson, which police never found a Cheryl Johnson with that phone number, which didn’t exist. Whatever Wayne was doing that night, I don’t know. Wayne possibly could be hiding something, or maybe Wayne did kill Nathaniel Cater, and maybe that’s why he and Jimmy are the only two murders he was convicted of.

Vincent Hill: Simply changing his story, it doesn’t prove anything, as far as why not years later, Wayne say, “Yeah, I lied. Here’s what I was really doing.” At the same time, you could argue and say why not years later, because let’s be honest, I don’t think Wayne will ever get out of prison, why not years later say, “Yeah, I’m gonna confess to everything, and here’s how I did it.”

Vincent Hill: Wayne’s entire existence is built on this. If he confesses, then that’s a wrap. Wayne Williams will just diminish. If Wayne confessed, he’s … Wayne was probably up to no good that night, but I don’t think it involved Nathaniel Cater.

Dale Russel: I don’t know that there was that defining moment during that trial. There was one for me as an observer that came at the very end, and I still think it was some of the strongest evidence that was presented in the trial, and I would tell you that 99.9% of your audience has never heard of it. The blood. Two of the last four victims were stabbed, at the end of the string of murders, John Porter and William Barrett. There were two blood stains found in the Station Wagon. They typed them. Neither one of them were Wayne’s blood, but they both matched the two victims that had been stabbed, Porter and Barrett.

Newscaster 2: The link was suggested by showing the jury this ripped-up car seat. It came from the 1970s Station Wagon driven by Wayne Williams. An expert from the Georgia Crime Lab told the jury that she had found four areas of dried blood on the seat. Two types were analyzed, Type A and Type B. Prosecutors then had witnesses testify about blood samples taken from the bodies of John Porter and William Barrett, two victims found with stab wounds. Porter had Type B, Barrett Type A, the same as the samples found in the suspect’s car. The jury also heard the dried blood in the car could not be from Williams, since he was Type O, the state obviously suggesting that the bodies of Barrett and Porter were at one time on that seat.

Newscaster 2: Of course the defense wanted the jury to realize the connection is a shaky one, since Williams’s parents and the owners of the car and uncle and aunt and thousands of other people may have had those blood types and driven in the car.

Dale Russel: If you could get to the blood, I think, if I recall, it was within six weeks, you can break it down even further. You get into an enzyme factor. They were able to do that. Both of those two victims had been stabbed within the last six weeks. Both of the two blood stains in the back seat of Wayne Williams’s car were fresh enough to be able to break them down into the enzyme factor. Both matched Barrett and Porter.

Newscaster 2: Prosecutors continue to close in with a connection. The jury, listening carefully and taking notes, heard that both Porter and Barrett had an enzyme Type 1, a further breakdown of their blood samples. The panel then heard that both stains in the car were enzyme Type 1.

Dale Russel: One of them, according to the testimony in the trial, that particular blood type and enzyme factor was found in only 7%. I can’t remember if it was 7% of males or 7% of African American males, but it was 7%. The other one was found in only 24%.

Newscaster 2: Talking percentages, the witnesses said only seven out of every 100 people would have Porter’s Type B enzyme Type 1, and that 24 out of every 100 people would have Barrett’s Type A enzyme Type 1.

Dale Russel: Two victims stabbed, two blood stains in his car, and they both match. It was physical evidence. That’s not really circumstantial evidence. That’s physical evidence. It’s not a fingerprint, it’s not a murder on a videotape, but it was very strong evidence I thought at the end of that trial.

Payne Lindsey: Throughout my investigation, the case of Clifford Jones kept popping up. Jones’s case stands out in particular because many people feel there’s another viable suspect for the murder, aside from Wayne Williams. I first found DeWayne Hendrix from a YouTube video of Clifford Jones’s brother, Emmanuel.

Dewayne Hendrix: Your brother’s name was?

Emmanuel Jones: Clifford Jones. It was one early morning, August 20, 1980. People had kidnapped my brother. A man named Jamie Brooks, Horace [Hopgood 00: 29: 48], Freddy Cosby, these guys held my brother captive in a laundromat right on the corner of Hollywood Road.

Newscaster 3: Hours later, he was found near a dumpster behind the mall, strangled, wrapped in plastic.

Dewayne Hendrix: His brother was inside, being beaten and raped all day, before they actually killed him and disposed of his body.

Newscaster 3: An alleged eyewitness described the strangling of Jones and identified the strangler, not Wayne Williams, but a man named Jamie Brooks.

Dewayne Hendrix: He knew that Wayne Williams didn’t kill his brother. He knew that.

Newscaster 3: Despite all that evidence, the task force blamed Clifford Jones’s murder not on Jamie Brooks, but on Wayne Williams.

Newscaster 4: The investigators reviewing the case file on Clifford Jones released to Channel Two News under court order a file containing statements from five eyewitnesses who point to a suspect other than Wayne Williams as the killer of Jones.

Payne Lindsey: Jones’s case also stood out to fiber analyst Larry Peterson. To Peterson, Jones’s case was one of the only puzzles he couldn’t put together.

Larry Peterson: Clifford Jones’s case became I think important in my mind, one, because it was the first one I went to. It was the one that seemed to be to cement the need to force a task force.

Larry Peterson: At this crime scene, one of the things I did was examine the body, look around the body, are there tire prints, are their shoe prints, is there anything from a crime scene standpoint. Literally there was nothing but the body itself. One of the things I’d noticed and collected was over 20 beige carpet fibers, loose in his hair, on his skin, on his clothes, and I collected them at the crime scene. That was one of the fiber types that I’m convinced is important, because they were so loose and so many, they had to be tied to how his body got there.

Larry Peterson: Whatever sample came in, that was one of the ones I would always go with. It was the green carpet, there were some other things, but in this case, I always look for those beige carpet fibers on any sample submitted for comparison.

Larry Peterson: Actually, through the trial, they never matched anything. That was always a mystery fiber as to then where did they come from. It bugged me through post trial. It always had bugged me. The thing that I wanted to know most was I wanted to know everything about what the evidence meant.

Payne Lindsey: A year after trial, to satisfy his own professional and scientific curiosity, Larry, investigated further. He couldn’t reconcile these missing pieces.

Larry Peterson: They had put these records into evidence that they had these three different Ford Fairmonts, 1984 Fairmonts the family was getting, using as rentals.

Payne Lindsey: This was news to me. It turns out between ’79 and ’81, the Williams family was in possession of at least six cars at one time or another, three being rental cars.

Larry Peterson: I was at Fulton County about a year after the trial, and I went by the appeal attorney’s off and talked to Joe Drolet. I said, “Is there any way, if the defense put those rental agreements into evidence, is it possible I could get copies?” He supplied me with copies of the rental agreements, which include VIN numbers and descriptions of the automobiles. I took that and I ran it through our crime information center. Through the vehicle registration, it came up with the fact that those had been sold as used cars. I had GBI agents go to those locations, collect trunk liner and floorboard fibers from those three rental cars. In the meantime, I looked at the time sequences of when the rental agreements were and what victims disappeared in those time sequences.

Larry Peterson: Clifford Jones fell into the same time sequence. When that fiber sample came in from the trunk liner and from the floorboard, the first thing I found was that there were beige carpet fibers in the floorboard of the 1980 rental car that matched the Clifford Jones fibers.

Meredith S.: Wow.

Larry Peterson: I had a stronger case after the trial than I even did during the trial.

Payne Lindsey: What he found during his investigation was the beige carpet fibers, the ones he could never match before trial, the ones that link Clifford Jones to a car in Wayne Williams’s possession.

Larry Peterson: One of those things where everything built on everything else that came after it. Nothing ever eliminated him. Nothing ever eliminated Wayne. Everything we would come to kept him in the ballpark. Lewis Slaton said at the beginning of the trial, “It’s a puzzle, and we’re gonna put all the pieces together.” As you watch that puzzle being filled in, they answered every question for the jury. It’s a case to me that its strength was in the totality of all of it.

Jim Procopio: Does he have any defense lawyers? He had a good one for a while, Jack Martin. Jack’s a good attorney. I think if Jack saw something here or didn’t see something here, that’s why he’s not involved anymore. I think everybody’s lost interest in Wayne. They realize that he’s the right guy. I don’t see much happening on the Wayne Williams front.

Larry Peterson: The bridge made it, the fibers made it, the blood made it, the eyewitnesses made it. It was everything. They told you what Wayne’s life was and how it fit into all this, of his taking these cars and driving for hundreds and hundreds of miles, driving in the late night, early morning hours, picking up young boys, gonna be a music producer, never really producing anything. They gave the jury a picture of who this guy was.

Monica Kaufman: The story of Wayne Williams is one story, because he was charged and convicted with the murder of adults. That’s one story. The other story, the children, the girls, the boys who were murdered, who were dumped.

Larry Peterson: How do you introduce evidence from another crime that the defendant’s not charged with? Georgia law allows you to bring in what they call a similar transaction. It was a two-part test. You had to prove to a judge that there was some evidence linking the defendant to the crime and there was some evidence that the crime would show a pattern, a scheme, and a bent of mind of that defendant. Oh my god, this is what Lewis Slaton’s going to do with Wayne Williams, and we’re going to have the child murder trial. It’s not gonna be Jimmy Ray Payne and Nathaniel Cater.

Monica Kaufman: I would say that whatever law Lewis Slaton used at that time period, it was probably the most expedient thing to do. If there were enough similarities, then just dump it all on one. That’s not criticizing Mr. Slaton. It’s just saying it appeared at that time to be the best thing to do.

Larry Peterson: It gave the public, and again, it answered a question in the jury’s mind, what about the kids? They gave, I believe, Atlanta the child murder trial.

Jim Procopio: As I said before, the guy was anonymous, no one’s seen him, no eyewitnesses. It is amazing we convicted him without any eyewitnesses. Not a single person came forward. The witnesses that we had were very shaky at best. They thought they saw this and they thought they saw that. I was not involved with the trial, but again, it was all hairs and fibers. Today it would be a very interesting case.

Newscaster 2: Wayne Williams told reporters at a press conference in June that he didn’t know any of the victims on the task force list.

Reporter 1: You knew none of them?

Wayne Williams: No.

Reporter 2: Did you know the victims at all, adults or otherwise?

Wayne Williams: No, I didn’t.

Reporter 3: No associates, no family?

Wayne Williams: None.

Newscaster 2: The state has witnesses that will place the victims with Williams. The nextdoor neighbor of the Williamses did say he saw Wayne the day the suspect was supposed to be with victim Larry Rogers.

Newscaster 2: Two relatives of the victim said Wayne Williams was seen with Barrett several months before his death.

Newscaster 2: More damaging testimony today from other witnesses who claim to have seen Cater alive on May 21st. One woman placed the suspect with Terry Pue, but in April of last year, five months after Pue’s body was found.

Newscaster 2: Margaret Carter, a woman who lives in Northwest Atlanta, told the jury that she saw Williams with victim Nathaniel Cater in this Verbena Street park a week before Cater’s body was found in the Chattahoochee River. The witness also said alongside the two men was a German shepherd. The person who stood out as the most credible witness was this woman, Nellie Trammell, who placed Wayne Williams in a car with Larry Rogers, saying the slightly retarded man was slumped over in the passenger seat. A week later, Rogers’s body is found near Simpson Road.

Wayne Williams: A lot of the witnesses indeed were unreliable, because people gotta remember, when this case came to trial, there was a half-million-dollar cash reward out for information leading to the arrest and conviction of anyone associated with the Atlanta killings. It’s obvious by the testimony that several of these witnesses were motivated when they thought that they would be able to collect reward money for their testimony.

Newscaster 2: Ken Lawson worked in the taskforce headquarters answering phones and writing reports, but Lawson was amazed to see Nellie Trammell as a witness, telling the jury the elderly woman was almost a regular at taskforce headquarters, who would sit there for hours knitting. Every time a body was found, she’d call about it. It got to the point, he said, that recruits would try and pass Nellie’s calls off to each other.

Wayne Williams: Some of the witnesses were just plain wrong. One guy was a 89-year-old guy who could not see.

Newscaster 2: An elderly man who may have been discredited by the defense because of poor eyesight testified he saw Williams with Payne last April.

Wayne Williams: Identified me with I believe it was Jimmy Ray Payne on Bankhead Highway from a distance of a quarter a mile away, and he couldn’t even identify me in the courtroom, so it was laughable. Another witness came into the courtroom and admitted just before testifying he had just smoked weed.

Newscaster 2: Another witness, nicknamed Cool Breeze, putting Williams with Larry Rogers, was an admitted drug user, and in fact told the jury he had smoked marijuana before testifying. His credibility was strained.

Wayne Williams: He wasn’t able to pick me out on the witness stand, so he pulls out a piece of paper out his pocket, said, “Yeah, but I seen this guy in the newspaper.” It was ridiculous. It was ridiculous. On the other hand. You did have some witnesses who were just plain wrong in their association. One of those witnesses, Kent Hindsman, thought that he saw Joseph Bell at a recording studio that we had on January 3rd.

Newscaster 2: Kent Hindsman, a 24-year-old songwriter, says he spent most of January 3rd with Williams in this Buckhead recording studio.

Newscaster 2: There with Williams was a teenager by the name of Joseph Jo Jo Bell.

Kent Hindsman: I remember Jo Jo because he came in and he’d sing a few tunes. He had a very good voice. I was asking Wayne what was he gonna do with him. Wayne said he was gonna sign the guy to a contract immediately.

Wayne Williams: At the same time you had another state witness testify that she saw me with Lubie Jeter on that same day as the recording studio session was held.

Newscaster 2: A middle-aged white woman, Ruth Warren, told the jury she also saw Williams with Jeter the day the 13-year-old boy disappeared.

Wayne Williams: He provided a alibi for me, because we were at a recording studio in Buckhead, miles away from where Lubie Jeter disappeared. You had state witnesses conflicting with each other.

Newscaster 2: The witness could not remember under cross-examination when she told police about the sighting.

Tony: This story can help y’all out. Whatever y’all podcast about, that’s cool, man, but this shit 100, what I’m telling y’all.

Payne Lindsey: Recently, a man named Tony came to the office and told me a story he’s only ever told his family.

Tony: I ain’t making up none of this, man. This shit for real. I ain’t trying to get no nigga in trouble who shouldn’t be talked about or put no lies on nobody. It’s true facts.

Tony: Me and my cousin, we was going to the Atlanta Zoo, so we had rode bikes over there. We snuck in the zoo, matter of fact, with one of them little back gates where it turned one way or the other. We slid through. We had chained our bikes up outside. When we came back out through, the bikes were gone.

Tony: We were basically right there just puzzled more like how are we gonna get back home. Where I was living then, it was a project, it was called Grady Homes. I was walking back across the park, going back to Grady Homes.

Tony: Out of the blue, this guy came off the top of the hill. He was like, “Hey, what’s going on? How y’all doing? You okay?” I was like, “Yeah, we fine.” I said, “Somebody done stole my bicycle. We was over at the zoo, and now we gotta walk back home.” He was like, “You need a ride?” I was like, “Nah, we good. We can walk.” He was like, “My daddy is the pastor of this church over here.” It was a little housing area, so I remembered that church because I had been over there. I was like, “Yeah, I’ve been to that church before.” He was like, “Yeah, my daddy the pastor.” He said, “He’ll take y’all home. Y’all ain’t got to walk all the way back to Grady Homes.” I was like, “Cool, then.”

Tony: We was following him back to the church, thinking his daddy was gonna give us a ride. Instead of him taking us straight across the street to the church, he took us to the street and took us up a pathway in the back of the houses along the street that led to the church.

Payne Lindsey: That’s when things started to feel a little weird.

Tony: Why you taking us this way? I felt fishy about why he took us through this pathway. By the time we got back to where the church is at, off the street, there was a car parked there, so he was more like, “Y’all go on and get in the car. I’m fixing to go get my daddy, and daddy gonna take y’all.” I was like, “Nah, we just gonna wait until your daddy come.”

Payne Lindsey: The man got antsy and aggressive, and Tony knew something wasn’t right. He had to get out of there.

Tony: I was like, “I gotta pee.” I pissed on the side of the car. My cousin Bobo was standing by the car beside me. He was telling my cousin, “You just go on and get in.” He was like, “Nah, we ain’t gonna get in. Just go get your daddy.” He started looking around.

Tony: When he stepped back to the car again, he had opened the car door, that’s when he got aggressive. His whole demeanor changed. His whole thing was get us in this car. It turned from, “My daddy fixing to take y’all home,” to, “Y’all get y’all motherfucking asses in this goddamn car.”

Tony: He had grabbed us, in the back of a church, when nobody else was around. He tried to throw us in the car. For him to try and get two at a time was a task. We tried to break loose and we started hitting on him. He couldn’t let one get away and keep one, so he had to reach two people in two different direction. That’s how we broke away. He lost grip on one, lost grip on the other one.

Tony: We split up. I ran one way and my cousin ran back the way we came. I look back, and I’m running, I don’t see nobody behind me, so I’m thinking he probably got my cousin. I’m running up the street crying, get way up there. Then all of a sudden my cousin come out, he pop up. I said, “How the hell you get away?” He said, “Shit, I just kept running. He ain’t come behind me.”

Tony: I went back to the house. I was telling my mom. I was like, “A guy just tried to throw us in the car, tried to kidnap us.” I took them where the car was parked. I took them where he took us to. The car was gone. The only description I had then was that he favored my brother, 5’6″, 5’7″, with glasses.

Payne Lindsey: Tony told his mother that the dangerous man that tried to abduct him looked kind of like his own brother, a black man with bushy hair and glasses. At first, the man was nameless, but then Tony saw the news.

Tony: A year or so went by. My mama and them was looking at it on the news. I was like, “That’s the same guy who tried to grab us, ma.” The guy who did it, I remember his face clearly. Everything came together. When I saw his face, I knew that was him. Wayne Williams. She was like, “You sure?” I said, “That’s him. I’ll never forget that guy.” I said, “Remember I told you he looked just like Red?” I said, “Now don’t he look like Red?” She was like, “Yeah, he do favor Red a little bit.”

Tony: That’s him. I’ll never forget his face, because we fought with him. It ain’t no mistaking no identity. I can picture that whole day clearly. I looked this man in his face. This man tried to abduct me. I know he tried to abduct us. It wasn’t like he was playing. He got real serious. He tried to put us in this car.

Payne Lindsey: In hindsight, Tony realized the man’s gestures were actually manipulative and calculated charm, a way to lure prey without suspicion.

Tony: If I would’ve been by myself, he probably would’ve killed me. He might’ve took our bikes. He might’ve saw us come there and took our bicycles, so he knew that we were gonna have to walk back. He could’ve killed me. People believe different type of ways, but I know for a fact that he tried to do to me. I know how conning and conniving he is it ain’t nothing to trick somebody in the car with him.

Payne Lindsey: To Tony, it all made sense, all the stories about Wayne Williams. He says he saw it firsthand.

Tony: He wasn’t coming at you like a monster. He was coming at you like a friend, to get your trust, to get you in that car. That’s why he did what he did for so long, because he didn’t make no scene doing what he was doing. It was so normal how he’ll get you in that car. Wouldn’t nobody recognize it.

Tony: I seen how he tried to do us. You probably wouldn’t even have been talking to me today. Real talk. I’m telling you real. I ain’t benefit nothing from this. My family knew about it is all. I don’t talk about this to nobody.

Tony: He ain’t come at you like no beast to get your attention. He ain’t pull up and hit you in the head with a baseball bat and throw you in the trunk. That ain’t how he worked. They was already from a low-income family, probably ain’t had too much food in the house. Anything could persuade them, a candy bar, ice cream.

Tony: Man ain’t got no remorse. That man don’t care. He ain’t sitting back in prison really crying he’s innocent. He ain’t really fighting that hard to let folks know he need to be out of prison. He just doing his time, because they know he killed them other children. They just can’t prove it. He did that, man. He’s a monster. I know he a monster. He killed a lot of babies. Shit’s sad, man.

Payne Lindsey: I thought it was only fair to share this story with Wayne to see what he said about it. Tony made a lot of bold claims, but very convincingly. I asked Wayne for his take.

Payne Lindsey: He came into my office a few days ago and he told me that he thinks that you tried to abduct him and his cousin at the back of a church.

Wayne Williams: A back of a what?

Payne Lindsey: Back of a church. He said that the man said that his dad was a pastor at the church.

Wayne Williams: That’s ridiculous. That’s one thing throughout this trial. You’ve got people who come forth with these stories after the fact. You’ve gotta remember, after my picture was flashed all over the news on June the 4th, you had all types of people coming forth saying, “I know this guy.”

Wayne Williams: My point is, where were these people before? Where were these people when these incidents happened at the time? They couldn’t identify anybody. Now I’m not saying that somebody may not have tried to abduct these people at all, but what I’m saying is that there’s enough scientific evidence, we know the data proves that witness testimony can be tainted and influenced by publicity after the fact, and that’s no doubt what happened in this case and with a lot of these witnesses.

Payne Lindsey: Is that story true?

Wayne Williams: Absolutely not. That’s ridiculous right there. I don’t even know these people, and here we are years later. I hear stories like that, again, we’ve heard it all through the years, but my point is, if it was true, these people would’ve come out a long time ago.

Wayne Williams: One thing I developed over the years from this thing, Payne, I’ve developed tough skin. I’ve heard everything. I’ve heard even the jokes and everything. I’ve heard it all. That doesn’t faze my resolve to get the truth out, because the fact is is that I’m innocent of what happened in Atlanta, Georgia. That’s the main focus that I’ve got to have right now.

Payne Lindsey: Tony’s story wasn’t the only one I was told. There was one more.

Anonymous Male: Don’t be his lawyer. Don’t be his savior. Don’t be his god, because I know what I seen with my own eyes. At this time I was staying on one side of town, the Bankhead side of town. We had moved from Grant Park, and my aunt still stayed there. One Sunday I went over there to play with my cousin. I’m at Grant Park. We was at Grant Park playing.

Anonymous Male: Then when I left, instead of me waiting on the bus at Atlanta Avenue, I went up by Atlanta Fulton County Stadium, and I was sitting in the bus stop waiting on the bus. Then a big blue Chevrolet pulled up, stopped in the middle of the street, and he let the window down. He said, “Hey, can you tell me how to get to Martin Luther King?” He said, “Where you stay at?” I said, “I stay on Bankhead, but I’m fixing to get ready to go.” He said, “I’ll give you a ride.” I said, “No, I don’t need no ride.” I sat back down in the booth. I heard some car tires. I get back up and looked. He whooped the car around in the middle of the street. This on a Sunday in front of Fulton County Stadium, wasn’t no game, so buses run slow, ain’t hardly nobody moving. I’m like, “Ain’t no more cars coming by.” He whooped back up by the bus stop and run up on the sidewalk.

Anonymous Male: I jump up, and I was looking at the sketch, looking at the sketch in the back of my mind, like, “This same dude be on TV.” I stood up at looked. At first I did jump back, like, “Is this for real?” I’m looking at him, and he step out with one leg and his little afro stick up in the air. He looked me dead in the face with the glasses on. I’m like, “Bro, really got to be kidding, because they already saying they looking for you, and you still out playing.”

Anonymous Male: I had told him I didn’t need no ride. I had told him where Martin Luther King was. If you from Atlanta, he didn’t really have to turn around right there. He could’ve went down to the red light, made a right, and went to Martin Luther King. When he pulled the car around, he pulled up on the sidewalk like he was trying to kidnap me.

Anonymous Male: I can’t be the judge of what Wayne did, but only thing I can say if somebody say, “He didn’t kill all them children,” that’s why I be standing here saying today, “Wait, pump your brakes.”

Anonymous Male: Everybody in the project knew they was poor, so we didn’t even fight each other like they do now, gangs. We didn’t fight each other. You from the projects, you poor like me, ain’t got no reason to fight. If we hear something about Wayne, your mama gonna call my mama, “My nextdoor neighbor said Wayne Williams had tried to get her son.” That was the conversation back then. They was saying Wayne Williams. They wasn’t saying no man in the blue car. Wayne Williams. They were calling him by his name. It’s real to me. You ain’t offer me no money. You ain’t offer me nothing. I’m just telling you what happened for real. We was already as kids preparing for if he came or when he came. Guys start buying little pocketknives and stuff, get a piece of glass and wrap it up in a napkin, put it in your pocket. If you ever got in trouble, somebody pulled up on you, tried to get you, that was your weapon.

Anonymous Male: Listen, man, listen, I’m not trying to debate with nobody, never, about what I seen or what happened to me. I don’t need nobody to run up on me 20 years later saying, “You said Wayne … ” I know what I seen. I don’t have to keep on trying to rehash it like I’m trying to convince nobody. I know Wayne. I done seen Wayne since then. Shook Wayne hand just to get in front of him, be like, “Bro, you done seen me before.”

Anonymous Male: In ’89 I was a young little risk dude, I’d done caught my first dope case, went down the road. Man, they put some dope on me. They said, “Dude up in the law library will help you out.” When I went up there and seen who it was, I was like, “Nah, I can’t let him work on my case.” That was just me.

Anonymous Male: Wayne was working in what they call the law library. Wayne in there. He done tricked the folks, saying, “I’m smart. Let me work in your law library.” When you go in the law library, you got a dope case, Wayne making friends with the dope boys, because he need really protection, like, “If I get in good with some of y’all, I can get the rest of these folks off my back,” because everybody got kin people in here. He is like the poor people’s lawyer by him working in there with the books. Every time you see him, he reading a book. You had guys in there who didn’t have lawyer money.

Anonymous Male: I was like, “I’m smart. I’m fixing to go to college,” so I started working on my own case. I’m sitting there. Wayne just like y’all sitting there, another inmate, Wayne. He ain’t killed nobody in my family or got people saying he didn’t do it. When he see you and said, “What you in here for, little bro?” you might not know he Wayne Williams though, you be like, “Man, they planted some dope on me.” That’s how you broke, “They planted some dope on me. That wasn’t even my dope.” That was right up his alley, “Now I can work on his case and build my friendship up, and I can get people to stop saying I’m gonna kill him.”

Anonymous Male: What Wayne would do is look over your case for you, be like, “Yeah, we gonna file this habeas corpus right here and get your case overturned. You gonna go home.” Wayne was in there helping people. When you in there, Wayne is your friend, because guess who is your enemy? The system.

Anonymous Male: Everybody in there was like, “When I see him, I’m gonna kill him.” If you got 31 children missing, that means you got 34 kinfolks in there, cuz and nephews and brothers, “When I see him, I’m just gonna choke him.” They couldn’t get to him like that. When you go to the law library, you sign a piece of paper, and they handcuff you, take you up there, and they open the door and throw you in there. You be like, “Shit, Wayne might kill me up in the library. He might be done made a shank and put it in the law library book.” He got a razor in the book, he could choke you, you know what I’m saying, if he’s a killer. What man want to face a serial killer knuck to knuck?

Anonymous Male: One day, dude come in there, and I want to say he was from Capitol Homes. I remember we were having a little small conversation. He was like, “I’m gonna get him. I’m gonna get him.” I guess that little kid, Toby Jeter or somebody from Capitol Hill that got missing some time he turned the corner in the library, and you ain’t hear nothing but pow!

Anonymous Male: I was looking around, and Wayne was picking the glasses up off the ground, dude had tears coming out his eyes. It just was something on his mind he wanted to get off. Like he wanted to fire off on Wayne.

Anonymous Male: We didn’t ask for this life. But for the Food Stamps and the welfare and the WIC and the government cheese and the powdered milk, like we had apartment and the lights was on, but wasn’t no pharmacy in there, wasn’t no food in there. Where we gonna get it from?

Anonymous Male: One part of history I don’t know, somebody gotta tell me who started first hating? It had to be one of two people. It couldn’t have been Jesus. Somebody had to start hating. Hatred and racism, they never taught us that in school. Until a bunch of us get together and start knocking at the door and have our own million man march with blacks and whites, not no riots and protests, I don’t want you to go to jail for me, if we don’t come together as we, like I said, we can have these conversations every week if we feel like it’ll make a difference, but this the Wayne Williams show. We need another show, if we want to break the race relations.

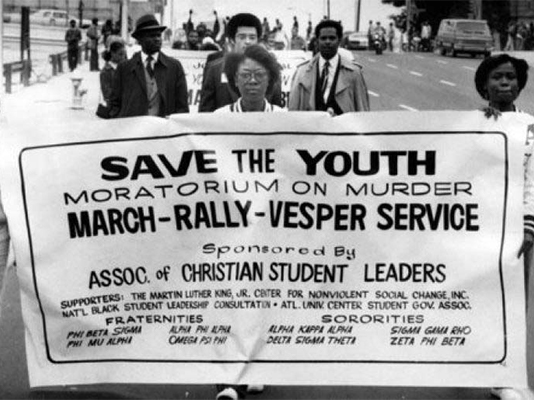

Payne Lindsey: If there’s one thing I’ve learned throughout my work on Atlanta Monster, it’s that no matter how you slice it, this story is bigger than an investigation, bigger than a trial, and bigger than Wayne Williams. This case evokes deep emotions, even in people that weren’t directly affected by the killings. From what I’ve seen, it’s inextricably tied to a feeling of social struggle. No matter who committed these crimes, the people of Atlanta, particularly the black community, didn’t feel safe or sufficiently supported. Through sensationalized media and heightened pressure, the children that were murdered almost seem to become a secondary narrative to the story of Wayne Williams. It’s most important to remember how this all started, with Edward Hope Smith on July 21, 1979.

Wayne Williams: I think podcasts such as what you’re doing, Payne, are one of the best ways to attack this misinformation and try to get people to open their eyes and see, “Wait a minute. It’s time to wake up and seek the truth.” You tried to tell a very difficult story, and you’ve done as best a job as you could telling that, so I guess that speaks for itself, because after all, Payne, you tackled probably one case that very few of us understand, and I commend you for trying.

Payne Lindsey: Who is the Atlanta Monster?

Wayne Williams: We don’t know. We really don’t know. I think that it’s clear at this point there was never any single Atlanta Monster. I think that your monster’s probably a group of some of these white supremacists who were involved in some of these killings. I think your monster is probably people involved in some of these sex and drug rings that no doubt kill some of these victims. I think your Atlanta Monster may really be the streets of Atlanta in the cases in which the victims were victims of street crime. I think instead of Atlanta Monster, you probably need to relabel it Atlanta Monsters and put a plural on the end of it.

Payne Lindsey: Wayne, did you murder anybody?

Wayne Williams: No, I have not killed anybody in my life. Payne, that’s a question people ask all the time. It’s a question that I welcome people to ask, because let me tell you something, I can look people in the eye because my soul is at rest with God. I sleep very good at night, because we’ve all done things in our life that are wrong and we’re not proud of. There are probably a million things that I’ve done in my life that I could’ve been arrested for, but killing somebody isn’t one of them. I think anybody who really knows me and knows my character knows that this is a situation that was trumped up against me, so I sleep good at night.

Vincent Hill: It’s this murder mystery that never ends. As you know, there are just so many questions.

Monica Kaufman: We’re fascinated by crime stories. This is never going to go away unless someone is arrested and found guilty of killing one or two of these children and then somebody else is arrested and found guilty of killing a child. No, it’s never gonna go away. Even then, it won’t go away, because there will still be people who say, “I don’t believe he did it.” This is a story that will last longer than the two of us.

Calinda Lee: There is this growing sense that if we don’t figure this out now, maybe we never will. Is this going to go into some Jack the Ripper style vault of perpetually unsolved mysteries?

Monica Kaufman: I don’t think it’s opening up an old wound because I think the wound is healed, because many people say, “Wayne Williams is in jail, and that’s it.” I think what it’s doing is informing a new generation, because there are a lot of people who have never heard of this case, because they weren’t born when it happened.

Monica Kaufman: Now it serves two purposes, the historical perspective, two, it also opens up new minds to investigate the case. Then three, it reminds young people, you can’t run footloose and fancy-free all over the city and think someone’s not gonna grab you, although we’ll never know why those particular children were taken. They were poor. They were black. They were in a poor part of town, alone. Right now they’re still alone. They are alone in that no one seems to bother about saying, “I really want to know who killed Lubie Jeter. I really want to know what happened. Who’s been holding something inside for all these years?”

Calinda Lee: For many of these children, the way that they were characterized suggested to people, “There’s no reason for you to cry for yourself, because they don’t have to mean anything for you, and you don’t have to cry for them and what they lost either,” because that wasn’t going to amount to anything much. That to me is not only tragic and upsetting, it is simply untrue. It’s not true for anybody.

Kasim Reed: It felt heavy. That’s how it felt. It felt sad. It felt like there was a very terrible person, indeed a monster, who was just devouring black men.

Payne Lindsey: This is former Atlanta mayor Kasim Reed. His term in office just ended this year.

Kasim Reed: I was mayor for 2,920 days.

Payne Lindsey: He remembers the child murders firsthand as a young boy growing up in Atlanta.

Kasim Reed: There needs to be an equality to the importance of life. To the extent that you have real equality of the importance of life, you would’ve have more attention faster if it were a white child. Any child that’s harmed, we ought to have the same level of intensity and passion and focus from day one. There should not be a lag time for alarm. It needs to be that a kid got killed, and we’re gonna find who killed the kid and we’re gonna bring that person to justice.

Kasim Reed: It needs to be a unified feeling that that is the case. It should not be community by community. To the extent that we do that, we are a better city. We have to maintain that important ethic that our children are hands off to anybody, and that anybody who attempts to harm our children will suffer extraordinary, dynamic, and extreme consequences, with unified support. That’s what I hope that the lesson will be.

Payne Lindsey: Thanks for listening to Atlanta Monster. If you’ve enjoyed it, I encourage you to check out our first podcast, Up and Vanished, a true crime investigation into the disappearance of Georgia high school teacher and beauty queen, Tara Grinstead. Up and Vanished is available now on Apple Podcast.

Payne Lindsey: Atlanta Monster is a joint production between How Stuff Works and Tenderfoot TV. Original music is by Makeup and Vanity Set. Audio archives courtesy of WSB News, Film, and Videotape Collection, Brown Media Archives, University of Georgia Libraries. For the latest updates, please visit AtlantaMonster.com or follow us on social media. If you have any questions for me or the team, please call us at 1-833-285-6667. That’s 1-833-285-6667.

More Episodes

Episode 8

CIA

What car did Wayne really drive? Where did the reward money go? And was Wayne scouted by the CIA?

Episode 9

The Trial

Trial by trace evidence.

Episode 10

Loose Ends

In this case, the truth depends on who you choose to believe.